Psychiatric disorder is more common than we may think. One such common disorder, which could be linked to our increasingly busy, isolated and stressful lives, is bipolar disorder. What is bipolar disorder, what happens in the brain, and how do friends and loved ones help a person who may suffer with it?

By Dr Samantha J. Brooks Ph.D.

Bipolar disorder – a mood disorder characterised by polar

extremes of mood – was once known as “manic-depressive disorder”, which sheds light on the symptoms of this often debilating psychiatric condition.While it is normal to experience fluctuating periods of happiness and sadness associated with usual life circumstances, a

person diagnosed with bipolar disorder will have triggered swings from extreme

happiness and high levels of energy, to extreme sadness and hopelessness,

within a matter of hours or days. Extreme happiness presents as mania, such

that a person becomes excessively active in behaviour and speech, finds it

difficult to sleep or sit still without fidgeting, and may have racing thoughts

and ideas that fly quickly through the mind in illogical succession. A person in the manic phase may take more

risks, such as being more sexually active, taking drugs or spending more

money. Compare the manic phase to

extreme sadness, where a person may experience debilitating depression and

limited energy. During the depressive

phase a person may sleep all day and feel as if everything in their world is

hopeless, with no motivation to change things. Both extremes are like a see-saw

for the individual with bipolar disorder, who will likely experience no sense

of organisation or control over their life. The extremes of bipolar disorder

are associated with fluctuating neurotransmitter levels in the brain – a

significant rise in dopamine levels for mania and a significant drop in

serotonin and opioid levels for depression.

Less extreme versions of this debilitating condition – that often see

people eventually losing their jobs, becoming withdrawn and not engaging in

everyday activities – are known as hypomanic states.

Bipolar disorder – a mood disorder characterised by polar

extremes of mood – was once known as “manic-depressive disorder”, which sheds light on the symptoms of this often debilating psychiatric condition.While it is normal to experience fluctuating periods of happiness and sadness associated with usual life circumstances, a

person diagnosed with bipolar disorder will have triggered swings from extreme

happiness and high levels of energy, to extreme sadness and hopelessness,

within a matter of hours or days. Extreme happiness presents as mania, such

that a person becomes excessively active in behaviour and speech, finds it

difficult to sleep or sit still without fidgeting, and may have racing thoughts

and ideas that fly quickly through the mind in illogical succession. A person in the manic phase may take more

risks, such as being more sexually active, taking drugs or spending more

money. Compare the manic phase to

extreme sadness, where a person may experience debilitating depression and

limited energy. During the depressive

phase a person may sleep all day and feel as if everything in their world is

hopeless, with no motivation to change things. Both extremes are like a see-saw

for the individual with bipolar disorder, who will likely experience no sense

of organisation or control over their life. The extremes of bipolar disorder

are associated with fluctuating neurotransmitter levels in the brain – a

significant rise in dopamine levels for mania and a significant drop in

serotonin and opioid levels for depression.

Less extreme versions of this debilitating condition – that often see

people eventually losing their jobs, becoming withdrawn and not engaging in

everyday activities – are known as hypomanic states.

It is important to remember that victims of domestic and

emotional abuse may appear – or are led to believe that they are – behaving in

a manner akin to bipolar disorder, and if this is happening to you it is vital

to seek urgent support. A correct diagnosis of bipolar disorder does not stem

from a disgruntled partner, an ex or a psychopathic boss, who may gain pleasure

in causing upset and confusion – a manipulative tactic known in modern parlance

as gaslighting – but rather stems from meeting strict criteria in the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Version 5 (DSM-5). The DSM-5 can be relied

upon – as the bible of psychiatrists – to determine real cases of psychiatric

disorder, so that the individual sufferer can receive vital treatment (such as

pharmacotherapy or counselling) to improve their quality of life. The DSM-5 recognises four main types of

bipolar disorder. The first is Bipolar I

Disorder, where manic episodes last for at least 7 days and severely consume

the energy resources of the individual, to the point where they may need

hospitalisation. Depressive symptoms usually co-occur for around 2 weeks and

may also be present during episodes of mania.

The second is Bipolar II Disorder, which is defined as a successive

pattern of unprovoked depressive symptoms and hypomanic states that cycle for

at least 7 days, and might even surprisingly occur at the same time. The third is Cyclothymic Disorder (also

called cyclothymia), defined by numerous periods of hypomanic and depressive

episodes lasting consecutively for at least 2 years (1 year in children and

adolescents). Finally, Unspecified Bipolar Disorder is a catch-all category,

where a person may exhibit episodes of mania or depression, but not usually

within the same timescales as the main diagnoses.

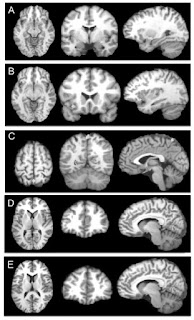

What then, are the neuroscientific bases of a DSM-5

diagnosis of bipolar disorder – in other words, which brain regions are more

activated in the MRI scanner? Recent studies of bipolar disorder have

demonstrated, particularly in response to emotional stimuli like faces, that an

over-active connectivity occurs between the amygdalae and prefrontal cortex –

brain regions associated with arousal/fear and goal-directed behaviours

respectively. This suggests that people with bipolar disorder may not be able

to effectively self-regulate their emotional responses to their

environment. Such hyperactivity in the

brain may also be associated with learned responses that began during

significant past trauma, or may even be due to the increasingly stressful, busy

and socially-isolated lives we lead today.

For example, chronic trauma, stress and social isolation (e.g. due to

long working hours and parental separation) may cause a downregulation

(reduction) of opioid receptors in the brain – the locks to the pain-relieving

brain hormone keys. Opioids are the brain’s natural defense to pain – including

emotional pain – and so if chronic emotional pain is experienced, opioids may

become less potent over time. We also

release opioids and other hormones, such as oxytocin, during intimate

pair-bonding. If emotional and/or

physical abuse is chronically experienced, a person may begin to exhibit more

and more signs akin to emotional dysregulation and bipolar disorder.

And so, if you are a friend or family of a person who may be

exhibiting manic or depressive coupled with periods of low

energy and hopelessness, in a cyclical pattern over long periods, with no

obvious cause, it might be useful to do the following. First, gently communicate with the person, to

try to establish if there are serious, underlying causes for this behaviour,

such as physical or emotional abuse (don’t simply assume that they are suffering

from bipolar disorder). Be prepared that

the person may not wish to open up immediately, but be supportive and

accepting. If no obvious cause for the

behaviour is established, then the second step might be to suggest the person

visit a psychotherapist, to talk through with a trained professional who can

establish the cause. Finally, with the

help of the therapist, a formal diagnosis for the behaviour can be established

and treated, usually with a combination of suitable medication and further

psychotherapy.

And so, if you are a friend or family of a person who may be

exhibiting manic or depressive coupled with periods of low

energy and hopelessness, in a cyclical pattern over long periods, with no

obvious cause, it might be useful to do the following. First, gently communicate with the person, to

try to establish if there are serious, underlying causes for this behaviour,

such as physical or emotional abuse (don’t simply assume that they are suffering

from bipolar disorder). Be prepared that

the person may not wish to open up immediately, but be supportive and

accepting. If no obvious cause for the

behaviour is established, then the second step might be to suggest the person

visit a psychotherapist, to talk through with a trained professional who can

establish the cause. Finally, with the

help of the therapist, a formal diagnosis for the behaviour can be established

and treated, usually with a combination of suitable medication and further

psychotherapy.

The ultimate take-home message is this: don’t be quick to

give a layman’s diagnosis to a person who may exhibit symptoms akin to bipolar

disorder, as there may be other reasons for their behaviour. However, if a formal diagnosis by a trained professional

is established, a person suffering with bipolar disorder has a wealth of

treatment options available to him or her, that can enable them to continue

living a fullfilling, enjoyable life! We

must always remember: life is too short and too precious to cause - or

exacerbate - human suffering!

Dr Samantha Brooks is a neuroscientist at the UCT Department

of Psychiatry and Mental Health, specialising in the neural correlates of

impulse control from eating disorders to addiction. For more information on neuroscience at UCT

and to contact Samantha, see www.drsamanthabrooks.com. Note: Images royalty

free, courtesy of https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki.