Panic stations are upon us – the water crisis deepens and Day Zero is fast approaching. But what can neuroscience tell us about the brain processes of panic, and how we can get a handle on them?

Panic stations are upon us – the water crisis deepens and Day Zero is fast approaching. But what can neuroscience tell us about the brain processes of panic, and how we can get a handle on them? By Dr Samantha J. Brooks Ph.D.

These days in Cape Town, raw emotions are running high as we are reminded daily that our water supply is running out. The taps in our homes could soon – if day zero arrives – be turned off. It is a prospect that fills people’s cognitions with fear and leaves us questioning, “how did we get here?”.

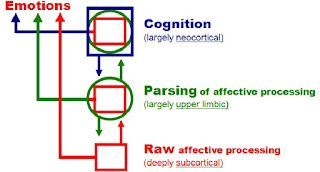

The thought of losing our vital, life-affirming water supply has contributed to the emergence of the water guzzler sub-species of folk, who we continue to hear about in the local news despite disaster being imminent. These folk continue to behave in this way, because our emotions parse with and hijack our cogntions, and fear transforms into panic. Desperate times call for desperate measures, as the water guzzlers take a narrow perspective to ensure that their homes - regardless of the water restrictions applied to everybody else - have plenty of water. Panic is inevitably fueled by raw, affective rage – and people not only act in denial (which is also a river in Egypt with lots of water!), but also begin fighting each other as they fill their 25 litre cannisters. The basic negative emotions (also known as affective states) of FEAR, PANIC and RAGE are what the late, great neuroscientist, Professor Jaak Panksepp called primary processes, which are common to animals too.

Humans however, can choose to exert control over these primary processes (which originate from activation of mid-brain areas, such as the amygdala), by exercising secondary processes of learning and memory (found in the hippocampus) that strengthen tertiary processes to remember our future intentions and exercise self-control (in the prefrontal cortex). But what are the practical steps that we can take to exert control over our primary processes during this water crisis?

We need to remember the bigger picture perspective if we are going to alter our water consumption habits and quell the natural tendency to descend into behaviours fuelled by fear, panic and rage. We can consciously pay more attention to our relationship with water, and use small amounts to wash, shower over a bucket and use the short eco-cycle on the washing machine once a week. By taking conscious control in this way, we will find that our primary emotions of fear, panic and rage begin to lessen, and we may avert the arrival of day zero.

But what if day zero actually comes? Capetonians must remember that the tertiary processes in the prefrontal cortex of the brain are what allow us to keep control of ourselves. If we must adhere to new, unfamiliar rules, such as the daily collection of 25 litres of water, it will be our prefrontal cortex that enables us to adapt to this rule and survive. Our prefrontal cortex - if we practice to be conscious of our water usage habits now – will learn how to regulate primary emotions and keep fear, panic and rage at bay. And our secondary processes in the hippocampus brain networks will help us to remember how precious our short supply of water is. In the end, perhaps the whole world will learn from Capetonians, about how to use our brains to cope with the emotional consequences of a changing climate.

Dr Samantha Brooks is a neuroscientist at the UCT Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, specialising in the neural correlates of impulse control from eating disorders to addiction. For more information on neuroscience at UCT and to contact Samantha, see www.drsamanthabrooks.com.